Go (game)

Go (game)  Basic rules

Basic rules

Basic rules

Two players, Black and White, take turns placing a stone (game piece) of their own color on a vacant point (intersection) of the grid on a Go board. Black moves first. (If there is a large difference in strength between the players, Black is sometimes allowed to place two or more stones on the board for his first move, see Go handicaps for details). The official grid comprises 19?19 lines, though the rules can be applied to any grid size; 13?13 and 9?9 are popular choices to teach beginners.? Once played, a stone may not be moved to a different point.

?

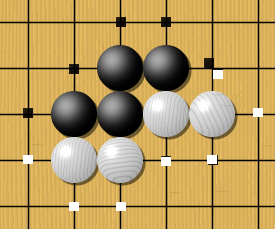

Vertically and horizontally adjacent stones of the same color form a chain (also called a group) that shares its liberties (see below) in common, cannot subsequently be subdivided, and in effect becomes a single larger stone. Only stones connected to one another by the lines on the board create a chain; stones that are diagonally adjacent are not connected. Chains may be expanded by playing additional stones on adjacent intersections or connected together by playing a stone on an intersection that is adjacent to two or more chains of the same color.

A vacant point adjacent to a stone is called a liberty for that stone. Chains of stones share their liberties. A chain of stones must have at least one liberty to remain on the board. When a chain is surrounded by opposing stones so that it has no liberties, it is captured and removed from the board.

Most rule sets do not allow a player to play a stone in such a way that one of their own chains is left without liberties, subject to the following important exception. The rule does not apply if playing the new stone results in the capture of one or more of the opponent's stones. In this case, the opponent's stones are captured first, leaving the newly played stone at least one liberty. The rule just stated is said to prohibit suicide. (Since suicide is very rarely useful, making it legal does not significantly alter the nature of the game.)

Players are not allowed to make a move that returns the game to the position before the opponent's last move. This rule, called the ko rule (from the Japanese ? k? "eon"), prevents unending repetition. See the example to the right: Black has just played the stone marked 1, capturing a white stone at the intersection marked with a circle. If White were now allowed to play on the marked intersection, that move would capture the black stone marked 1 and recreate the situation before Black made the move marked 1. Allowing this could result in an unending cycle of captures by both players. The ko rule therefore prohibits White from playing at the marked intersection immediately. Instead White must play elsewhere; Black can then end the ko by filling at the marked intersection, creating a five-stone Black chain. If White wants to continue the ko, White will try to find a play that Black must answer; if Black answers, then White can retake the ko. A repetition of such exchanges is called a ko fight.

While the various rule sets agree on the ko rule prohibiting returning the board to an immediately previous position, they deal in different ways with the relatively uncommon situation in which a player might recreate a past position that is further removed. See Rules of Go: Repetition for further information.

Instead of placing a stone, a player may pass. This usually occurs when they believe no useful moves remain. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends and is then scored.